The Proas of John Pizzey - Part 1

John Pizzey may be an unfamiliar name to proanauts outside Australia, but we hope to correct that. John has been experimenting with proas as long or longer than any modern inventor, and he has an immense body of both practical and theoretical knowledge to share. Proafile is pleased to present the first article in a series, authored by John Pizzey. ~Editor

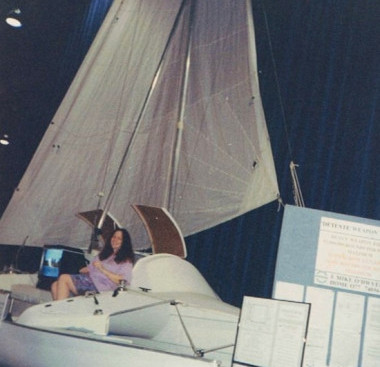

A few thoughts on cruising proas after many years absent from sailing them but hopefully about to get back to the misadventure. As can be seen from the literature, there are any number of possible rig, rudder and centreboard combinations that can be made to work, some easily, some needing a fair amount of skill and diligent attention. The trick is to get a combination that works well. If you can’t easily single-hand the boat I would question its usefulness Furthermore, there is obviously not only one correct solution, or for that matter any solution.

In three of my proas and in several guises I have sailed competitively in mixed fleets, such as the around the buoys Winter Series in Moreton Bay with several hundred monohulls and a few multihulls without causing chaos and in close company with many, mostly on Pi which we sailed frequently in bay and ocean races for more than a decade.

On Flight, my last sailing proa, a trailer sailer, virtually upon launching and untried, we competed in the trailer-sailer race from the Gold Coast to Brisbane up the very narrow passages at the bottom end of Moreton Bay for the first day and then into the more open part of the bay for the second, camping overnight on the boats. With the tide going out and against us at the start of the race we soon learned to continue on each tack until we hit the mud, then shunt, otherwise every inch and more that we made in the 50m dash across the passage we lost during shunting, boy that was hard work. We finished mid fleet.

On Pi, a float downwind proa, at the start of the Gladstone race we had to sail past a turning buoy to give us room for shunting. Unfortunately a monohull with an angry skipper was downwind and beside us and was most unhappy at not being able to tack immediately about the buoy. Such are the realities of sailing proas.

Who talks about navigation lights, has someone worked out a foolproof way of reversing the lights on each shunt? We have accidentally confused boats behind us by forgetting to switch the lights during a night ocean race, but more seriously late one night while racing from Brisbane to Mooloolaba in stormy conditions we saw an oncoming ship entering the port of Brisbane through the narrow marked passages alongside Moreton Island. We shunted to get out of his way and forgot, in the panic, to switch the lights, the skipper of the large ship did not realize we had reversed direction to head out of the passage and reacted by turning towards us, it was a bit scary until he veered back into the passage! After that, switching was automated. I had two tri-colour lights mounted one atop the other at the top of the mast. Accidents can happen sailing in adverse conditions, especially overnight, when everyone is tired and perhaps a little anxious. On a proa, its probably only the skipper who really knows the boat.

This leads me to the perfect proa design, when all else fails for whatever reason you need your cruising proa to automatically stabilize in an operative position from which you can easily recover in adverse conditions, no matter what your condition is, such as being blown towards a lee shore while totally exhausted or partially incapacitated (the frightening experience you are having may have sapped your strength) and many of us are not super fit heroes. It’s not a nice feeling and its worse if you think you have no hope sailing out of trouble.

The other requirement I believe essential is that there should be no requirements for special adjustments or manoeuvres before shunting. You need to be able to throw off the sheets instantly any time without laying off or adjusting centreboards etc. then shunt. If you can’t do this you will encounter a situation where you will get caught out. You also need to be free of concern about being caught aback.

I have built and sailed several proas over 7m, utilized many more rigs and rudder combinations with outrigger upwind and downwind and for my preference the above requirement rules out having the sails and centreboard on one hull as such a craft can sit with either hull downwind and with no immediate automatic tendency to pivot to an operative stable (and un-inverted) position from which you can recover by simply trimming the sails to move off in a desired direction.Even that effort in a dramatic situation may test your reserves. Of course the conditions don’t need to be bad as this - may also happen immediately after you weigh anchor in a somewhat crowded anchorage and cause you great embarrassment - total lack of control. Adventuring by sailboat often tends to bring you to an unexpected adverse incident from which, thankfully, most of us recover.

With the centreboard in one hull and rig on the other, the rigged hull will be blown around the centreboard hull and lie stably in the downwind position, hanging off the centreboard as a sea anchor. This further suggests centreboard in float (low windage) and cabin (large windage even with sails lowered) on leeward hull. A flying proa?

With a central daggerboard in the float and always down when sailing and not required to be adjustable and sails on the main hull it will be necessary to bias the centre of effort of the sails toward the front of the main hull so either a conventional central fixed mast rig with furling headsails each end is suggested or a mast which tilts forward in the direction of sailing is suggested and then the sail choice is limited to sails which will work on such a mast. This is all old hat to the original proa sailors with their wishbone rigs, they knew it all along.

One advantage of a conventional rig stood vertically, apart from its state of development, is that the proa could be sailed as a conventional multihull with a kite up. A blast with a kite is really something, certainly keeps you on your toes. The other advantage of a flying proa is that when caught aback, the heavy hull is upwind.

The simplest sail for a fore and aft pivoting mast is the isosceles triangle sail. I have tried several and they work, great for light winds but a bit hard to make work successfully in strong winds. Incidentally I have also tried a fully battened spinnaker-like sail, using 1.5 inch electrical conduit as battens. It worked, but oh boy, scary for life and limb when it accidentally flew from the masthead swooping hither and thither.

On my soft sails I installed a set of eyelets centrally down the sail to enable a slack flail line to pass therethrough from the masthead to a fore and aft strop along which the lower end could freely move. This kept the sail under control if released, folded about the flail line, should both sheets be released. Also when docking, with the sheet released the flail line could be tightened to operate the forward half of the sail, handy at times when just a little slow speed movement is required. The sail could then be reefed by tying up a bottom panel of the sail. The sail could also be lowered along this flail line. I also used this technique in a spinnaker for Flight, a most tricky undertaking. Ah the stories I could tell about racing and gybing downwind to round a mark, changing the spinnaker set from one end to the other with opposition boats under kites bearing converging to the mark. Try it one day and figure out how many lines etc you need. Again perhaps someone has worked it out and could share it with all who are interested. A bell-mouth and sock is another good start for controlling the spinnaker. I used that on Pi.