The Proafile Primer

GALLERY | Click images to enlarge

The illustrated glossary of bilaterally asymmetrical sailboats.

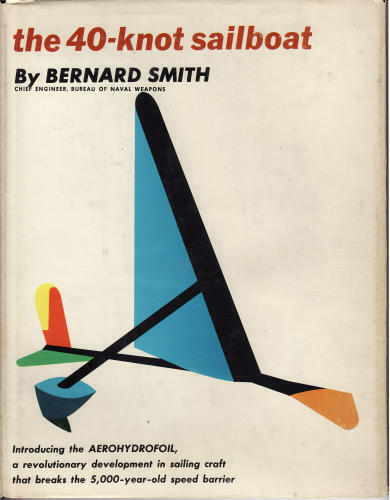

aerohydrofoil Sailboat concept pioneered by Bernard Smith in the 1960’s and described in his seminal work The 40-Knot Sailboat. Smith’s analysis of sailboat kinetics led him to a groundbreaking design involving no traditional sail or hull, instead utilizing solid airfoils and buoyant hydrofoils, arranged in a proa-like formation. Many of today’s proa advocates credit the excellent proa chapter with sparking their first interest in proas.

ama Polynesian for outrigger float or log, in common use among multihull designers.

aka Polynesian for outrigger cross beam.

asymmetrical hull Micronesian proa hulls are not symmetrical side to side. In section, the leeward side is flat, and the windward side is rounded and full-bodied. The keel line is offset to leeward. In some proas, the keel in plan view exhibits a slight convex bow to windward. Hull asymmetry improves the canoe’s windward ability, and counteracts the turning moment created by the drag of the outrigger log.

asymmetrical hull Micronesian proa hulls are not symmetrical side to side. In section, the leeward side is flat, and the windward side is rounded and full-bodied. The keel line is offset to leeward. In some proas, the keel in plan view exhibits a slight convex bow to windward. Hull asymmetry improves the canoe’s windward ability, and counteracts the turning moment created by the drag of the outrigger log.

“It is hard for one who has been accustomed to traditional naval architecture to think straight about the outrigger canoe. We in the West have always thought of a boat as bilaterally symmetric along a fore-and-aft centerline, that is, one side is supposed to be the mirror image of the other.

The outrigger canoe, with its strange appendage jutting out to one side, supported on its outer end with a smaller hull or a float, plainly violates this principle. I have heard people who should know better speak of the outrigger as an asymmetrical craft, but it really is not. The sailing outrigger canoe is just as symmetrical as our boats, but the axis of symmetry has been rotated ninety degrees.

Stand on the outrigger side of one of these canoes that has been correctly built and you will see what I mean. It is the two ends, rather than the two sides, which are exactly alike. These identical ends serve alternately as bow and stem, and the outrigger is always on the windward side when the boat is under sail.

Not only are these boats symmetrical, but that symmetry has a certain relation to the direction of the wind, and what could be more logical in a sailing craft?”

Euell Gibbons

The Beachcomber Afloat

Atlantic proa See Pacific proa. A term coined by the AYRS to differentiate a new hybrid proa design from the traditional "Pacific" model. There were never indigenous canoes like a proa in the Atlantic, the Atlantic proa being a modern invention developed for offshore racing. The Atlantic proa keeps its outrigger float to leeward, not to windward like a traditional proa. The outrigger float must become much larger and more buoyant than the traditional heavy log to work properly, and the boat in effect becomes a shunting trimaran with the redundant windward float removed, thus saving the weight and windage. Cheers, by multihull designer Richard Newick was the first and most famous Atlantic proa.

Atlantic proa See Pacific proa. A term coined by the AYRS to differentiate a new hybrid proa design from the traditional "Pacific" model. There were never indigenous canoes like a proa in the Atlantic, the Atlantic proa being a modern invention developed for offshore racing. The Atlantic proa keeps its outrigger float to leeward, not to windward like a traditional proa. The outrigger float must become much larger and more buoyant than the traditional heavy log to work properly, and the boat in effect becomes a shunting trimaran with the redundant windward float removed, thus saving the weight and windage. Cheers, by multihull designer Richard Newick was the first and most famous Atlantic proa.

AYRS Amateur Yacht Research Society. Founded in 1955, the AYRS boasts members from around the world, both amateurs and professionals. The society prints books and journals filled with research on all matter of sail craft, from hydrofoils to kite rigs. AYRS members have experimented with the proa form for decades, and have a searchable index of all proa articles. If you think you have a great new proa idea, better check the AYRS index first.

AYRS sail See Bolger rig.

balestron rig (Aerorig®, Easyrig®, swing rig) Perhaps the simplest way to get a sloop rig to work on a proa, this rig is similar to a Bermudan sloop, only the boom is extended forward of the mast, so that the tack of the jib may be attached to it, rather than to the bow. The mainsail and jib are trimmed simultaneously and automatically with one sheet, and it is possible for the main and jib to weathercock around 180 degrees during the shunt. The rig is most often freestanding, but it may also be stayed. Read Rig Options: The Balestron Rig

balestron rig (Aerorig®, Easyrig®, swing rig) Perhaps the simplest way to get a sloop rig to work on a proa, this rig is similar to a Bermudan sloop, only the boom is extended forward of the mast, so that the tack of the jib may be attached to it, rather than to the bow. The mainsail and jib are trimmed simultaneously and automatically with one sheet, and it is possible for the main and jib to weathercock around 180 degrees during the shunt. The rig is most often freestanding, but it may also be stayed. Read Rig Options: The Balestron Rig

Bolger proa rig (AYRS Sail) Designed by small boat designer Phil Bolger. This sail echoes the rotated 90 degree symmetry of the proa, in that it has an interchangeable leach and luff, and dedicated windward and leeward sides. Bolger writes:

“The battens and boom are permanently curved. For a proa, it is most appropriate to change ends, letting go the taut tack downhaul and hardening down on the other. The one not acting as a tack downhaul serves as the sheet. The sail is pivoted around the axis from the tack downhaul up to the head. Four-fifths of its area is abaft this pivot axis, so it will luff reliably (unlike a squaresail) when its sheet is started. It does not pivot on the mast and is attached to the mast only by the halyard."

Boats with an Open Mind

International Marine, 1994

Because of its obvious appeal, the Bolger rig has been tried by several proa experimenters - however so far, practice has not lived up to theory. Read Rig Options: The Bolger Rig

Bruce foil Invented by Edmond Bruce, this hydrofoil is designed not to lift a boat out of the water, but to dynamically stabilize it against overturning. It consists of an outrigger with a 45 degree canted hydrofoil at the end, instead of a float. The foil automatically and proportionally creates a stabilizing force that balances the heeling force of the sail. Bruce foiled boats can theoretically not be capsized by wind force, and simply accelerate in gusts, with no heeling. In practice the sea state, foil cavitation and ventilation, and control issues do limit the ultimate top speed. Proas are excellent Bruce foil platforms, either Pacific or Atlantic types. Read Proa Testing With Models

Bruce foil Invented by Edmond Bruce, this hydrofoil is designed not to lift a boat out of the water, but to dynamically stabilize it against overturning. It consists of an outrigger with a 45 degree canted hydrofoil at the end, instead of a float. The foil automatically and proportionally creates a stabilizing force that balances the heeling force of the sail. Bruce foiled boats can theoretically not be capsized by wind force, and simply accelerate in gusts, with no heeling. In practice the sea state, foil cavitation and ventilation, and control issues do limit the ultimate top speed. Proas are excellent Bruce foil platforms, either Pacific or Atlantic types. Read Proa Testing With Models

caught aback Being "caught aback" is what happens when the wind accidentally comes from the wrong side of the boat. This canbe either completely traumatic and lead to a capsize, or it can be a non-event, depending upon what sort of rig design the proa uses.

counterpoise See lee platform.

crab claw sail See oceanic lateen. The distinctive sail shape of the South Pacific, being a narrow, two-sparred triangle with a characteristic hollow cut-out of the leach. Canoes of Fiji and Tonga utilize the classic crab claw. The structure and basic geometry of the crab-claw rig are identical to the Oceanic lateen, the differences being a matter of degree.

crab claw sail See oceanic lateen. The distinctive sail shape of the South Pacific, being a narrow, two-sparred triangle with a characteristic hollow cut-out of the leach. Canoes of Fiji and Tonga utilize the classic crab claw. The structure and basic geometry of the crab-claw rig are identical to the Oceanic lateen, the differences being a matter of degree.

The crab claw rig has been tested in a wind tunnel by the famed aerodynamicist C. A. Marchaj:

"Even more startling is the extraordinary performance of the crab claw sail… which demonstrates its superiority to a Bermuda mainsail right from the close-hauled condition. Its superiority increases when the boat bears away, and on reaching, with the heading angle 90 degrees, the driving force coefficient of the crab claw rig is about 1.7, whereas that of the Bermuda rig is about 0.9. That is, the crab claw delivers about 90 per cent more driving power than the Bermudan rig."

Sail Performance

International Marine, 1996

The modern scientific validation of the crab claw has sparked new interest in this ancient sail form. Read Rig Options: The Crab Claw

flying proa Term used by European navigators to describe the indigenous sailing canoes of the Marianas island chain.

"More than those of any other island group, the sailing craft of the Marianas Islands, by reason of their swiftness and elegance, riveted the attention and aroused the admiration of every navigator who had the good fortune to see them. Their large sailing canoes came to be known as "flying proas" and one of the early names of the archipelago was "Islas de las Velas" from the great number of sails seen passing to and fro between the islands."

Haddon & Hornell

Canoes of Oceania

Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, Hawaii

Gibbons rig A variation on a square sail intended to mimic a crab claw - designed by Euell Gibbons circa 1950. It is designed to offer easier shunting for a single hander. It consists of a sail…

Gibbons rig A variation on a square sail intended to mimic a crab claw - designed by Euell Gibbons circa 1950. It is designed to offer easier shunting for a single hander. It consists of a sail…

"triangular in shape, with a long, light bamboo yard permanently fastened along one edge of the sail. A stout bamboo mast was stepped in the very center of the main hull, right on the sidewise axis of symmetry , and stayed in place with clothesline wire and turnbuckles.

The sail was hoisted up the mast by a halyard attached to the exact middle of the yard. The end of the yard that would be the forward end on the first tack was pulled down and fastened to what would be the forward deck on that tack, making the yard rise diagonally up and aft, the after end projecting behind and above the top of the comparatively short mast.

The sheet, the line with which the sail is handled, was fastened to the corner of the triangle opposite the yard, and led through a block on the afterdeck."

Euell Gibbons

The Beachcomber Afloat

This rig is receiving new attention from several proa developers lately, most notably Gary Dierking. Read Rig Options: The Gibbons Rig

iako arched crossbeams which fasten the floater (ama) to the hull of a Hawaiian outrigger canoe. On the web: Hawaiian canoe parts.

lee platform (counterpoise, lee pod) A platform that cantilevers out from the leeward side of the hull on Marshall and Caroline island proas. It is angled up away from the water, so that waves will not hit it while sailing. It is used to carry people and cargo, and ads auxiliary stability in the event of a knockdown. Some modern proas have enlarged the lee platform to allow more interior volume, and to create buoyancy to leeward that aids in capsize recovery. It is theoretically possible to design a lee platform that will allow the proa to self-right from a 90 degree capsize.

leeboard A popular solution to the problem of leeway with round-bilge hulls, a leeboard is a centerboard without a slot, hung over the side of the hull, not pushed through the bottom. A proa doesn’t need to have twin leeboards like tacking boats, since one side is always the designated leeward side. Leeboards that pivot fore and aft may be used to steer the boat, by moving the center of lateral resistance in relation to the sail. See weight-shift steering, Yakaboo.

leeboard A popular solution to the problem of leeway with round-bilge hulls, a leeboard is a centerboard without a slot, hung over the side of the hull, not pushed through the bottom. A proa doesn’t need to have twin leeboards like tacking boats, since one side is always the designated leeward side. Leeboards that pivot fore and aft may be used to steer the boat, by moving the center of lateral resistance in relation to the sail. See weight-shift steering, Yakaboo.

lifting rig Term used to describe a sailing rig that creates an upward aerodynamic force as well as a forward one. Traditional proa rigs are lifting rigs, and may help explain the reason for the proa’s legendary speed.

log See ama.

Micronesia Ethnographic area of Oceania north of New Guinea and east of the Philippines comprised of the Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands, Republic of Palau, Kiribati, and Guam. It is here that the Oceanic sailing canoe reached its highest development.

ndrua Fijian voyaging canoe that was the largest and finest craft ever built by the Oceanic peoples, some as large as 100’ long.

Oceanic lateen See crab claw sail, Oceanic sprit. Triangular sail common to many Micronesian proas. It is roughly equilateral in plan, sometimes with a curved yard. Oceanic lateens always have a boom, which Mediterranean or Arabic lateens rarely do. The sail is always set from a mast that is stepped in the center of the hull, and then raked forward, so that the heel of the yard is placed at the bow. The mast has three stays at the mast head: one led forward, one aft, and one (or more) to the outrigger. The geometry between mast, outrigger and shrouds creates a very stiff yet flexible truss that supports the sail and outrigger with the minimum possible structure (weight).

Oceanic lateen See crab claw sail, Oceanic sprit. Triangular sail common to many Micronesian proas. It is roughly equilateral in plan, sometimes with a curved yard. Oceanic lateens always have a boom, which Mediterranean or Arabic lateens rarely do. The sail is always set from a mast that is stepped in the center of the hull, and then raked forward, so that the heel of the yard is placed at the bow. The mast has three stays at the mast head: one led forward, one aft, and one (or more) to the outrigger. The geometry between mast, outrigger and shrouds creates a very stiff yet flexible truss that supports the sail and outrigger with the minimum possible structure (weight).

Oceanic sprit See Oceanic lateen, crab claw sail. Rig common to Polynesia, consisting of a vertical mast and curved sprit, supporting a narrow triangular sail with apex set downward. The rig is used for tacking canoes, but never for shunting proas, because the sail cannot be adjusted fore and aft like the Oceanic lateen. Shifting the sail forward of center is important to maintain helm balance with a traditional proa.

Oceanic sprit See Oceanic lateen, crab claw sail. Rig common to Polynesia, consisting of a vertical mast and curved sprit, supporting a narrow triangular sail with apex set downward. The rig is used for tacking canoes, but never for shunting proas, because the sail cannot be adjusted fore and aft like the Oceanic lateen. Shifting the sail forward of center is important to maintain helm balance with a traditional proa.

![]() ogive section Wing section derived from an arc of a circle. Commonly, the upper surface is curved, the lower surface flat. This foil is symmetrical front to back, with sharp leading and trailing edges. It is useful for proas because it need not be rotated 180 degrees for a shunt, like normal rudders must. Its efficiency is somewhat less than the more usual teardrop wing section.

ogive section Wing section derived from an arc of a circle. Commonly, the upper surface is curved, the lower surface flat. This foil is symmetrical front to back, with sharp leading and trailing edges. It is useful for proas because it need not be rotated 180 degrees for a shunt, like normal rudders must. Its efficiency is somewhat less than the more usual teardrop wing section.

one way proa Oxymoron sometimes used to describe outrigger sail craft that do not shunt, such as speed sailing boats like Crossbow I (pictured). See outrigger canoe. Online: Big Boat Speedsailing.

one way proa Oxymoron sometimes used to describe outrigger sail craft that do not shunt, such as speed sailing boats like Crossbow I (pictured). See outrigger canoe. Online: Big Boat Speedsailing.

outrigger canoe A canoe type found throughout the South Pacific and Indian oceans, stabilized by a small float or log that is held alongside and parallel to the canoe hull by a connective structure of a certain length. All proas are outrigger canoes, but not all outrigger canoes are proas.

Pacific proa A term created to delineate the traditional, outrigger to windward proa type from the modern Atlantic proa derivation.

Polynesia Ethnographic area of Oceania bounded by a triangle formed by the islands of Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island. The proa was virtually unknown here, as was shunting. Tacking outriggers and double canoes were used. There is good evidence that in Cook’s time, the great shunting ndruas of Fiji were being copied by neighboring island groups, and replacing the older double canoe design because of its superior sailing qualities.

Polynesia Ethnographic area of Oceania bounded by a triangle formed by the islands of Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island. The proa was virtually unknown here, as was shunting. Tacking outriggers and double canoes were used. There is good evidence that in Cook’s time, the great shunting ndruas of Fiji were being copied by neighboring island groups, and replacing the older double canoe design because of its superior sailing qualities.

popo Sailing canoe of the Caroline islands.

proa A single outrigger sailing canoe originating from the islands of Micronesia. They were first seen by European eyes during the voyage of Magellan in 1521. At that time, the graceful canoes were extremely numerous, and were greatly admired by any sailor who saw them. Capable of over 20 knots and of distant voyages over open ocean, the proa far exceeded any other sailing craft’s performance until the late 20th century.

proa A single outrigger sailing canoe originating from the islands of Micronesia. They were first seen by European eyes during the voyage of Magellan in 1521. At that time, the graceful canoes were extremely numerous, and were greatly admired by any sailor who saw them. Capable of over 20 knots and of distant voyages over open ocean, the proa far exceeded any other sailing craft’s performance until the late 20th century.

A traditional proa consists of a very slender canoe hull, often with a sharp keel and side-to-side asymmetry. Power to carry sail is derived from a heavy log slung parallel and to windward of the hull by an often elaborate system of beams and struts, all lashed together with twine. Motive power is a large Oceanic lateen or crab claw sail rigged to a pivoting mast that is stepped upon the canoe hull. Steering is via an oar or paddle, and as has more recently come to light, via weight shift of the crew. All proas are symmetrical end-to-end, and asymmetrical side-to-side, or opposite to all other sailing craft geometry. The outrigger is always kept to windward to oppose the overturning force of the sail, and is often kept flying above the water’s surface.

Parts of a Micronesian Proa

Parts of a Micronesian Proa

- Outrigger platform (aka)

- Outrigger float (log, ama)

- Hull (vaka)

- Lee platform (counterpoise)

- Mast

- Yard

- Boom

- Mainsheet

- Spilling lines

- Sail

Modern Western proas may be rigged identically to the traditional version, or more commonly, employ western style rigs and rudders, as well as modern materials and construction techniques.

riak Micronesian for shunt.

rudder An extremely useful invention unknown on native proas. Much creative thought by modern proa experimenters goes into adopting the rudder for use onto a shunting sailing canoe.

rudderboard (dagger-rudder, trim-tab daggerboard) A combination rudder/daggerboard invented by Dick Newick for the Atlantic proa Cheers. It consists of a daggerboard with a small trim-tab like rudder built into the upper trailing edge. Two boards are used in tandem, with the aft one pushed down to steer, the forward board raised.

rudderboard (dagger-rudder, trim-tab daggerboard) A combination rudder/daggerboard invented by Dick Newick for the Atlantic proa Cheers. It consists of a daggerboard with a small trim-tab like rudder built into the upper trailing edge. Two boards are used in tandem, with the aft one pushed down to steer, the forward board raised.

This arrangement puts the center of lateral resistance aft, which is where it happens to balance the aft location of the schooner rig’s center of effort. The forward board can be adjusted to fine tune the balance, for self-steering.

Contrast this arrangement with the Oceanic proa, which places the sail in the extreme forward end of the canoe, and uses no boards or rudders. The deep, sharp keel of a flying proa has the center of lateral resistance forward of the athwartship centerline, so the forward rig naturally lines up the rig and hull forces to maintain balance.

shunt Proas don’t tack, they shunt. Shunting is the act of swapping ends. The boat comes to a stop, the rig and steering device are reversed, and the boat gains way in the opposite direction. This action allows the boat to always keep its outrigger to windward. Shunting is the most daunting aspect of proa sailing to the Western mind, and requires an entirely different approach to sailing. Sailors are trained to always maintain steerage way during a tack, lest we risk being caught in irons, and thus get out of control. A proa comes to a compete stop during each and every shunt, and if designed properly, is always under complete control. It never heads directly into the wind, so it cannot be caught in irons.

shunt Proas don’t tack, they shunt. Shunting is the act of swapping ends. The boat comes to a stop, the rig and steering device are reversed, and the boat gains way in the opposite direction. This action allows the boat to always keep its outrigger to windward. Shunting is the most daunting aspect of proa sailing to the Western mind, and requires an entirely different approach to sailing. Sailors are trained to always maintain steerage way during a tack, lest we risk being caught in irons, and thus get out of control. A proa comes to a compete stop during each and every shunt, and if designed properly, is always under complete control. It never heads directly into the wind, so it cannot be caught in irons.

steering oar Micronesian canoe sailors use an oar for downwind steering courses, when the sail creates too much weather helm for weight-shift steering to be effective. Read The Case for the Steering Oar.

te puke (tepukei) Voyaging canoe of the Santa Cruz islands. These canoes exhibit some of the most fascinating geometry of all the south pacific sailing canoes.

vaka Polynesian for canoe.

wa’a Hawaiian for canoe.

waka Maori (New Zealand) for canoe.

wa lap Sailing canoe of the Marshall islands.

weight-shift steering Traditional proas are steered on all reaching and windward courses with no rudder, paddle, or steering oar at all. Steering is achieved in a similar way to the rudderless windsurfer, by adjusting the relative fore and aft positions of the sail center of effort and the hull center of lateral resistance. Rudders are problematic at best on a proa, and the Oceanic solution is to simply not need them. Doing away with rudders also does away with vulnerable underwater foils, and removes the hydrodynamic drag of the rudder, which is considerably greater than its small surface area would suggest.

weight-to-windward proa (W2W proa, Harryproa™) A recent variety of Pacific proa that positions most of the weight (crew, accommodations, stores) in the windward ama - to create the greatest possible righting moment for a given displacement.

Yakaboo In 1911, Frederic "Fritz" Fenger sailed from Grenada to St. Thomas - a distance of 500 nautical miles - in a 17’ x 39" decked sailing canoe, with no rudder. Yakaboo steered by balancing a fore and aft sliding centerboard against the yawl rig.

Yakaboo In 1911, Frederic "Fritz" Fenger sailed from Grenada to St. Thomas - a distance of 500 nautical miles - in a 17’ x 39" decked sailing canoe, with no rudder. Yakaboo steered by balancing a fore and aft sliding centerboard against the yawl rig.

Adjusting the lateral resistance to steer is essentially what the Micronesians do as well, and this canoe shows another way to go about it. See also: leeboard, weight-shift steering.